Hacking a Dead Spider-Man Mobile Game

I’ve never done any reverse engineering, mobile pentesting or game hacking. But this blogpost combines all three and tells the story of how I reverse engineered my childhood mobile game Spider-Man Unlimited, found a secret cheat menu and wrote a custom script to exploit it, as well as several other application controls, including the game asset compression.

Spider-Man Unlimited

Gameplay

The actual gameplay of Spider Man Unlimited is super simple - it’s a Temple Run clone that is Spider Man-themed. It’s an infinite runner where you have to dodge obstacles and defeat enemies. You can purchase different Spider Man variants from portals, which are essentially lootboxes. These variants have different stats and bonuses that ultimately affect the score you get from the run.

Story

The concept of the multiverse didn’t make its way into the cinematic Spider Man media until 2018 with the release of “Into the Spider-Verse”. But this game was ahead of its time in 2014 as far as Spider Man lore goes, because its entire premise was that the Sinister Six from different dimensions came together, requiring Spider Man variants from different dimensions to unite to beat them. Moreover, throughout the game’s lifespan it had time-limited events which brought additional Spider Man villains and characters into the fold, like the Symbiote World event.

Death

All good things eventually come to an end, and so the game was shut down in March of 2019, without a reason given for its demise. The most likely reason for its untimely death is licensing. Perhaps the license given to Gameloft for the Spider Man brand ran out and they either decided to not renew it, or Marvel decided to not renew it. Either way, the game servers were shut down and you simply couldn’t play it anymore.

Testing Setup

Virtualization

Android x86

Android x86 is a VirtualBox VM that essentially emulates an older version of Android and it does so really well. By default it runs applications compiled for x86, but you can also enable the native bridge and run apps compiled for ARM. The game ran almost as smooth as BlueStacks on this and the only reason it wasn’t perfect for my use case was because the addresses in memory, when emulating ARM, were different from what they should have been in a real ARM process. This is a big deal if you are trying to do dynamic instrumentation with Frida.

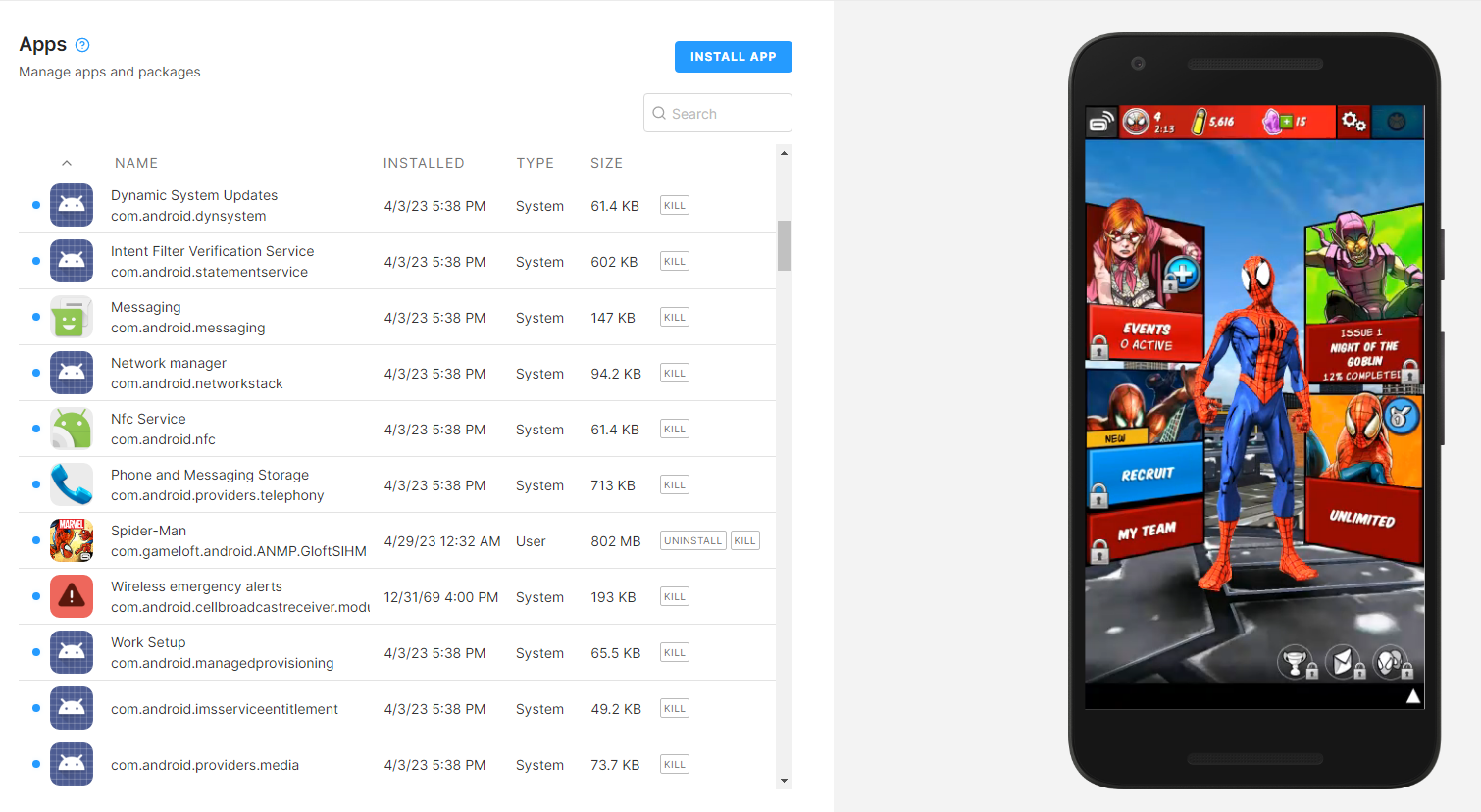

Corellium

Eventually I had to settle with Corellium as the better option for my application testing. Corellium is a paid online virtualization platform for phones. You can think of it as DigitalOcean, because you pay for core and storage usage. With Corellium you can deploy basically any type of phone, IOS or Android, and it will be jailbroken/rooted no matter the software version. Moreover, it comes with security testing software such as Frida, so it’s perfect for any vulnerability researcher or mobile penetration tester like me.

Decompilation

First of all, I was able to source an APK of the game from appchive.net, which conveniently has (!) 20 different versions of the game, which are free of malware, from what I could observe.

I used BytecodeViewer to open up the APK and view the decompiled Java classes instead of smali bytecode, which is a lot harder to analyze. I spent some time analyzing the Java code of the game and realized that all of its interesting functionality is hidden within the libSpidermanI.so library.

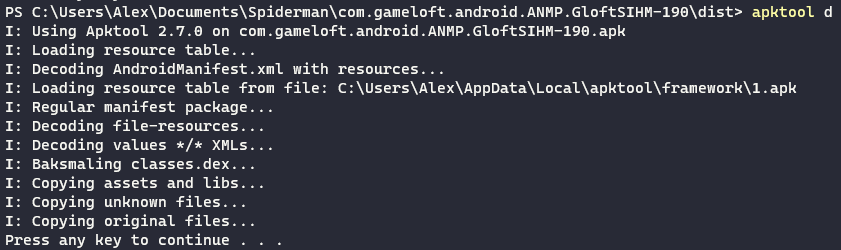

To pull the library out of the APK I first used apktool with the apktool d command. This tool decompresses the APK and separates its resources, as well as decompiles its Java code to smali. It creates the /lib folder for any shared libraries used by the app, which is where libSpidermanI.so is found for different CPU architectures.

After I extracted the ARM version of the libSpidermanI.so library, I used Ghidra, the reverse engineering toolkit written by the NSA. The binary seems to be missing things like function and variable names, so I had to manually go through and rename functions whenever I could based on its string literals. For whatever reason ARM turned out a lot easier to reverse than x86, because strings literals wouldn’t properly show up in x86 pseudocode.

Finally, after modifying the libSpidermanI.so library I would resign the APK back with jarsigner after rebuilding it with apktool b.

Version History

Current Issues

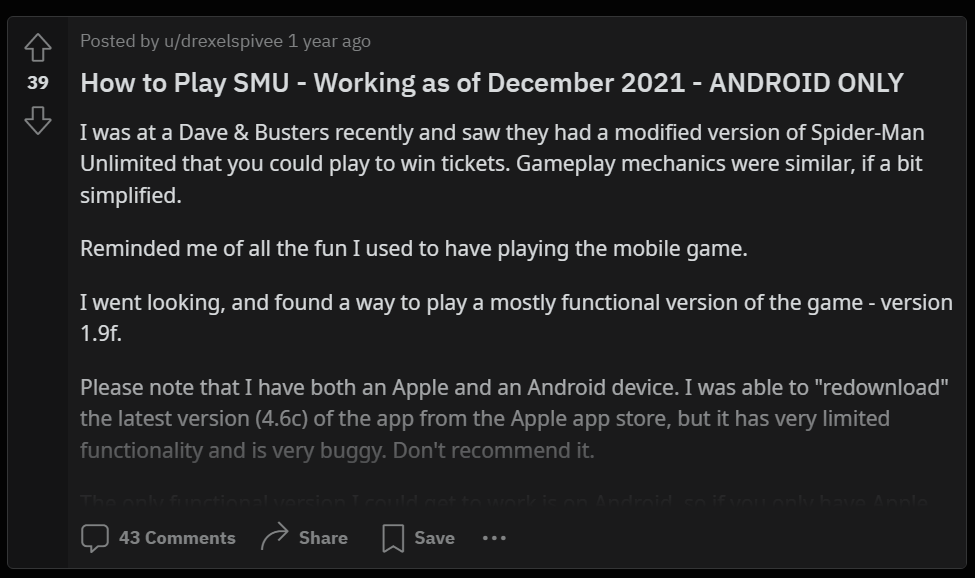

The last version to come out for this game was 4.6.0c and you can technically still download it from the AppStore if you go to your purchase history, or you can source an APK of it for Android. You can even start the game and get through the tutorial, but at a certain point you won’t be able to progress. Completing missions requires you to level up your characters, but all operations within the game that use currency are non-operational. This post on the Spider-Man Unlimited subreddit explains the issue.

Working Version

Turns out the game didn’t always depend on the Gameloft servers to be playable, as someone on the subreddit found that currency operations are still functional in the 1.9.0f version of the game. I pulled down the 1.9.0f build and was able to validate that it works if you follow the instructions from the post. I then also tried every single version above that from appchive.net, and confirmed that the server-side dependency exists starting from the 2.0.0 version.

The reddit post has a rather sizable list of steps you need to perform to play the game:

- Install the version 1.9.0f apk and get through the first tutorial scene

- Quit when the game gets back into the menu

- Disable automatic updates for the game in the Play Store

- Enable No-Root Firewall and block Spider Man Unlimited

- Change the device date to February 2019

- Disable the device internet with Airplane Mode

- Launch the game and enable internet

- Finish the tutorial levels

I was able to reduce this list of steps to just 2. First of all, because the game isn’t in the Play Store anymore, you don’t need to bother with disabling updates. Secondly, the firewall is useless when you disable internet. The device date is really the only relevant step here, because as I found through trial and error, the game will not function if the device date is set to December 31, 2019 or later. To play this game you simply need to install the 1.9.0f APK and change your date to sometime before the end of 2019.

Cheating History

Patched Binary

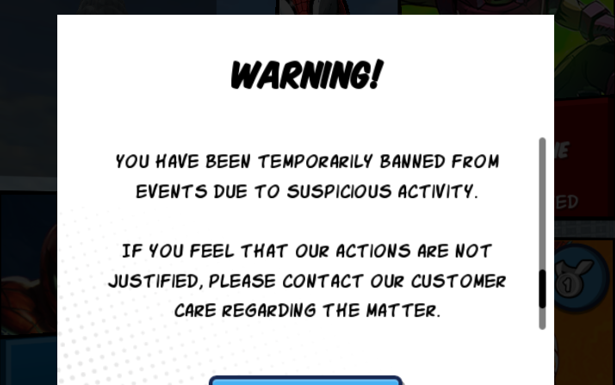

As part of my testing of all available versions of Spider Man Unlimited I came across a variety of APK’s sourced from all kinds of shady places. I wouldn’t be surprised if my Android emulator is running some kind of malware now. At one point I ran into an APK from HappyMod, which was different. Upon completing the game tutorial I saw that I had basically unlimited currency in the game. Alas, not everything was as good as it immediately seemed, because I was immediately banned from the game after completing the tutorial.

Patch Reversing

I set out to understand how the patch achieved this and first took the APK apart with apktool d. I then ran diff on the decompiled directory against a disassembled APK from appchive that I knew was unmodified and saw that there were no changes to the Java code of the app - all changes were contained in libSpidermanI.so. Armed with the vbindiff utility, I set out to understand what the patch did.

I found 5 differences between the patched binary and the clean one. One notable change was to the function located at the 002f493c offset. I started analyzing the function in the Ghidra disassembler and quickly inferred based on the string literals, that the function dealt with vials, the basic in-game currency. Among other things the function was doing some checks on the currency and granting achievements for spending a certain amount of it.

if (1999 < iVar3) {

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(iVar4 + 0x2dc);

funcConstructString(local_2c,"ACHIEVE_SPEND1000SC",auStack_38);

FUN_001bb1dc(uVar2,local_2c);

FUN_00fed030(local_2c[0] + -3,auStack_34);

iVar1 = local_30;

if (9999 < *(int *)(DAT_0125bfbc + 0x2c0)) {

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(DAT_0125bfbc + 0x2dc);

funcConstructString(local_2c,"ACHIEVE_SPEND5000SC",auStack_38);

FUN_001bb1dc(uVar2,local_2c);

FUN_00fed030(local_2c[0] + -3,auStack_34);

iVar1 = local_30;

if (49999 < *(int *)(DAT_0125bfbc + 0x2c0)) {

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(DAT_0125bfbc + 0x2dc);

funcConstructString(local_2c,"ACHIEVE_SPEND50000SC",auStack_38);

FUN_001bb1dc(uVar2,local_2c);

FUN_00fed030(local_2c[0] + -3,auStack_34);

iVar1 = local_30;

}

}

}

Similarly, the patch made changes to the function at the offset 002f4df4, which by process of elimination I identified to be dealing with the ISO-8 currency. And also to the function at 002f5784, which based on the string literals such as EnergyRefill, deals with the energy tokens used to run missions. We’re going to return to these functions in a bit.

Cheat Menu

Discovery

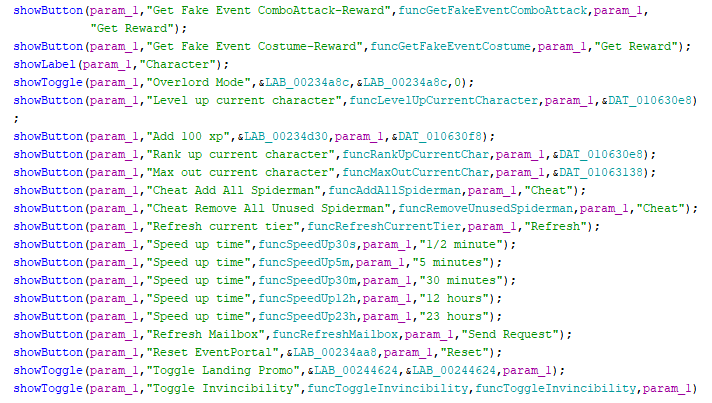

String literals are great for quickly understanding the context of a function in the decompiler. During my analysis I hit a goldmine when I searched for the word Cheat, because apparently the game developers left a secret cheat menu in the game code. The function that I named openCheatMenu neatly presented a set of buttons with labels and addresses of functions that they called. This made reverse engineering the game a lot easier, because I didn’t need to guess what the functions did.

The function at the offset 002f493c that I previously suspected to be dealing with vials, was included in this menu with a button labeled Gain Credits and the ISO-8 function was called by the Gain Cash button. I manually went through this cheat menu and renamed all functions in Ghidra to descriptive names based on their labels in the UI. It is a mystery to me how this highly sensitive code ended up in production, but I do appreciate it.

Testing

Discovering this code was merely the first step. The next was executing it. I tried to find references to the cheat menu function, but didn’t find anything. The developers left the code in the binary, but removed the means of accessing it in-game, probably thinking that would be enough to stop players. As you will see in a bit, this was not enough.

Recently I took a mobile penetration testing course and my instructors said “If you know how to use Frida, your imagination is your only limit”. I laughed at first, but now I know it’s true. Frida is a dynamic instrumentation toolkit that can be used to debug and test running applications across all platforms, including Android. Once you are connected to a device using adb, you can attach to a process using Frida as such:

PS C:\Users\Alex\Documents\Spiderman\frida> frida -U Spider-Man

____

/ _ | Frida 16.0.13 - A world-class dynamic instrumentation toolkit

| (_| |

> _ | Commands:

/_/ |_| help -> Displays the help system

. . . . object? -> Display information about 'object'

. . . . exit/quit -> Exit

. . . .

. . . . More info at https://frida.re/docs/home/

. . . .

. . . . Connected to Corellium Generic (id=10.11.1.1:5001)

Attaching...

Calling arbitrary functions with Frida is pretty simple if you are trying to access the Java code packaged with the APK. Unfortunately for us, all the juicy code is locked away in the libSpidermanI.so ELF library. Normally calling exported functions from a library is as easy as calling Module.getExportByName, but once again we are out of luck, because the library doesn’t expose any sensitive functions. If the function is hidden away in the library we must first overcome several hurdles to call it.

First of all, developers often strip debugging symbols such as function names from production code for performance and obfuscation reasons, so we can’t simply call one by name. Our only way of accessing a non-exported native function on Android is to call it by its memory address. We can retrieve the function offset from the Ghidra assembly view by locating the function and taking the leftmost value such as 0023b958 from the view.

Warning! Make sure that you go into Window > Memory Map in Ghidra and change the image base address to 0 by clicking on the “Set Image Base” button on the right. Otherwise your offsets will be wrong and all function calls with fail.

Now that we have an offset for the function, we must find its absolute address in memory. The function offset value is from the base address of the libSpidermanI.so binary in memory, so we must first get the library address using the Module.findBaseAddress Frida method. We need to then add the offset to that base address using the add() method. Finally, this is the syntax for finding an unexported function in memory with Frida:

Module.findBaseAddress('libSpidermanI.so').add(0x0023b958)

The next step is to construct a function prototype. We need to know what data type the function returns and exactly how many parameters it has and what their data types are. Thankfully we can get both in Ghidra from the decompiler view. For example:

void funcAddCredits(int param_1,int creditsAmount,int creditsSource)

In this example the function has 3 integer parameters and the void return type, meaning it doesn’t return anything. Based on this information we can create a NativeFunction object using Frida. The constructor for this object requires the pointer to the function (the absolute memory address we got earlier), the return type and the array of parameter data types. Here is how we can represent this function:

new NativeFunction(functionAddress, 'void', ['int', 'int', 'int']);

Now we are ready to call the function. Save the object to a variable and then call it like you would a normal function. Putting everything together, here is our short Frida script to access an unexported function based on its offset in Ghidra:

const functionAddress = Module.findBaseAddress('libSpidermanI.so').add(0x002f493c)

const addCredits = new NativeFunction(functionAddress, 'void', ['int', 'int', 'int']);

addCredits(exampleInt1, exampleInt2, exampleInt3)

I attempted to call the cheat menu function itself, but found that for whatever reason, that memory region wasn’t executable. I then performed these steps for all relevant cheat functions from the secret menu and was able to replicate all their functionality in game using Frida - unlock all Spiderman, get paid currency for free, etc. The next step was to improve the user experience of my cheat.

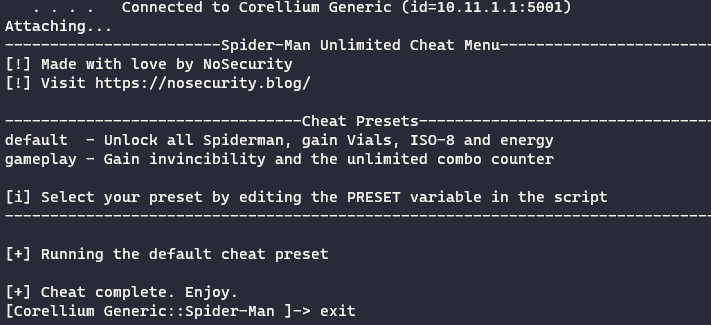

Scripting

Because pasting a long ugly oneliner into Frida isn’t quite peak user experience, I wanted to create a script that has all the cheat functionality I want. After collecting offsets and prototypes for 21 relevant cheat functions, I hardcoded them all into a Frida script and separated them into presets - default for unlocking all Spiderman and getting currency, gameplay for getting invincibility and unlimited combos. Unfortunately Frida’s JavaScript API doesn’t have any functionality for prompting for user input, therefore preset selection is made by editing the PRESET variable in the script. You can get my finished cheat script from GitHub.

Extras

Offline

Throughout my testing I noticed that the game really didn’t like my Corellium virtual instances. For whatever reason no matter the system settings, the game would pretend like my device was offline, locking most of its functionality and making testing a pain in the ass. I went back into Ghidra and figured this out.

First, when exploring how the game UI is drawn, I found that the function at offset 001bab24 was responsible for spawning message boxes in the game. I used that function in my script with the parameter of 0xc, which I sourced from the way I saw the game creating message boxes with text. After digging deeper into the decompiled code of the function, I found that it declares several other message box types. I manually called the function with the different type parameter and eventually found that 0x1a is the message box type that opens when your device has no internet access and tells you that you need to go online.

I labeled the function createMessageBox in Ghidra, began looking for references to it with the 0x1a parameter and quickly found what calls it. The function at offset 00143964, which I labeled showNoInternet created the message box as such:

createMessageBox(*(undefined4 *)(DAT_0125e9d4 + 0x6e8),0x1a);

It appears that this function was responsible for locking the buttons in the menu and creating the “no internet” popup when the device was offline. To circumvent this, I only need to make sure that this function is never called. I looked for references to it and quickly found what I was after:

if (((param_2 == 0) && (*(undefined *)(param_1 + 0xb0) = 1, DAT_0125e9d4 != 0)) &&

(*(int *)(*(int *)(param_1 + 0x49c) + -0xc) != 0)) {

showNoInternet();

}

The application was doing some comparison in the function at offset 00189c58. Notably, one of the required conditions for the showNoInternet function was param_2 being 0. So to make sure the function never gets called, I simply wrote a Frida hook that intercepted the function at offset 00189c58 and replaced the value of param_2 with 1.

The code for this is pretty simple. First, find the absolute memory location of the target function and declare its prototype based on information from Ghidra:

const checkInternet = new NativeFunction(Module.findBaseAddress('libSpidermanI.so').add(0x00189c58), 'void', ['uint32', 'uint32']);

Next, use the Frida Interceptor API to hook the function at that address and replace the second argument with a value of 1:

Interceptor.attach(checkInternet, {

onEnter: function(args) {

args[1] = ptr(1);

}

});

And now the game is playable offline! I added this hook into my cheat script for convenience.

Unpacking Game Assets

Kind of unrelated to cheating, I was curious where the game assets existed and if one can access things like graphics, textures, models and text strings that aren’t hardcoded into the libSpidermanI.so ELF. I found a directory with a large amount of suspicious .dat files in the following path on disk:

/sdcard/Android/data/com.gameloft.android.ANMP.GloftSIHM/files/

I was traversing the XeNTax forums when I stumbled upon threads related to decompressing unknown file types. People in the thread were discussing different QuickBMS scripts when this one galaxy-brain said “just use WinRar”. At first I thought it was a joke, but then I tested it and saw the truth - apparently WinRar is amazing at identifying and decompressing unusual compression algorithms. I was able to decompress and access a solid third of the game files.

I couldn’t open many of the .dat files with WinRar and started running strings on them. I saw XML with references to Adobe Flash, but the magic bytes of the file were that of an archive. So I asked ChatGPT to make me a simple script to change the magic bytes of a file to those of Shockwave flash:

#!/bin/bash

# Check if a file is provided as an argument

if [ -z "$1" ]; then

echo "Usage: $0 <filename>"

exit 1

fi

# Check if the file exists

if [ ! -f "$1" ]; then

echo "File not found: $1"

exit 1

fi

# Create a backup of the original file

backup_file="${1}.bak"

cp "$1" "$backup_file"

# Modify the magic bytes in the original file

printf '\x46\x57\x53' | dd of="$1" bs=1 count=3 conv=notrunc

echo "Magic bytes updated. A backup of the original file has been created: $backup_file"

The script worked like a charm and all the remaining files gave way. I was able to open them up in JPEXS Free Flash Decompiler and view all the graphics and scripts for the game menus.

Conclusion

Revival

If you happen to have reverse engineering skills and an interest in this game, please hit me up on Discord at NoSecurity#3039. There’s so much room for modding this game. Think about the possibility of server emulation and custom events/levels. If enough people connect with me and express interest, we can start a group to work on this further.

Credits

- Mandiant - for teaching me how to hack mobile apps

- drexelspivee - for figuring out how to play SMU in 2021

- XeNTaX - for galaxy-brain disassembly tips

- roundcube3 - honorable mention for inspiration

- Spider-Man Unlimited Fandom Wiki - honorable mention for dedication