Running a Discord Ransomware Gang

Have you ever wanted to build your own ransomware? I hope not. I am however fortunate enough to have an opportunity to be a menace on the red team of the Cal Poly Pomona SWIFT club’s Red vs. Blue competition. It’s very similar to CCDC and we’ve held it for years for talented Cyber Patriot teams from local high schools. For the first time this year we’re bringing it to our own school and we’ve built our own malware to spice things up for the Blue Teams competing. When learning a new programming language, one usually starts with “Hello World”, however that ain’t no fun, so I decided to learn Go by making Ransomware and things got a little out of hand.

Disclaimer: Ransomware is a serious issue and this blog merely serves educational purposes. To avoid giving script kiddies ammunition, I’m not publishing the full source code, only snippets. If you are looking to use this maliciously, please reconsider your life choices.

Design

My initial idea for this project was to have a ransomware payload that uses Discord webhooks to communicate successful encryption along with all the details, such as the decryption key. Problem was, however, this isn’t an OPSEC-safe way to run a ransomware gang because of the nature of webhooks.

Discord webhooks are a way to send a notification to a channel without authentication. As long as you have the URL, sending messages is as simple as curling a POST request at it. Two major problems come out of that webhook nature though:

1) If the blue team gets a hold of the executable, they may reverse it to find the Discord webhook URL 2) If the blue team sniffs with Wireshark, they may get the webhook URL even if it’s encrypted inside the payload

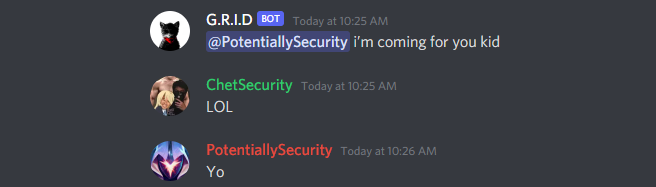

Having a rogue webhook is not as bad of an issue as having the blue team get a Discord bot token, because with a webhook they may only send messages. This issue can easily be mitigated pre-emptively by revoking the webhook immediately after the payload fires. This way, if the blue team sniffs or reverses the payload and gets the webhook URL, it’s too late to use it, because it’s already invalid. For this exact reason I decided to also make a Discord bot that would handle the webhook cleanup:

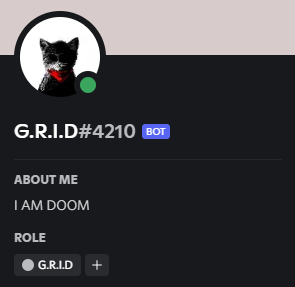

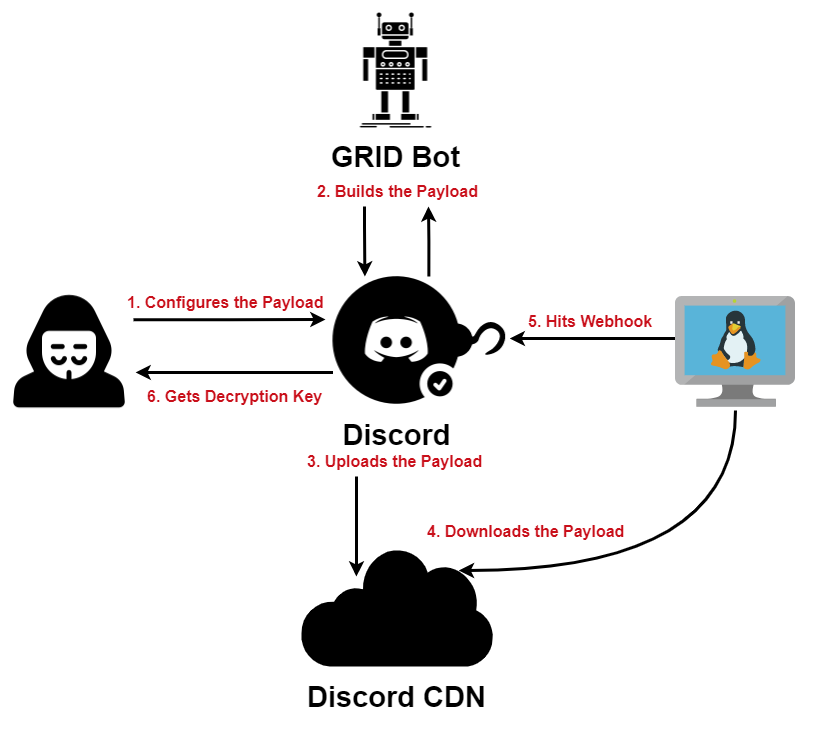

Meet the G.R.I.D bot. It runs the backend of our ransomware infrastructure and manages payload distribution. This jolly fella builds the ransomware payloads when the Red Team requests them and is controlled via Discord messages. When the bot builds a payload, it drops it into the Red Team channel and that stores the file on the Discord CDN. Red Team may then simply copy the link and wget it on the victim machine. Forget Python’s SimpleHTTPServer, Discord will host our malware for us. Overall, here’s the architecture we end up with:

1) Red Team configures the payload and sets the ransom message, as well as the directories that will be encrypted 2) 2) G.R.I.D bot builds the executable using the configuration provided by Red Team and sends the executable in a message 3) 3) The executable sent to the channel gets uploaded to the Discord CDN and Red Team copies the download link for it 4) 4) On the victim machine Red Team downloads and runs the payload from the Discord CDN 5) 5) When the payload executes, it generates a decryption key that gets sent along with other metadata to a webhook 6) 6) The information sent to the webhook is then relayed to the Red Team along with the victim ID

The Bot

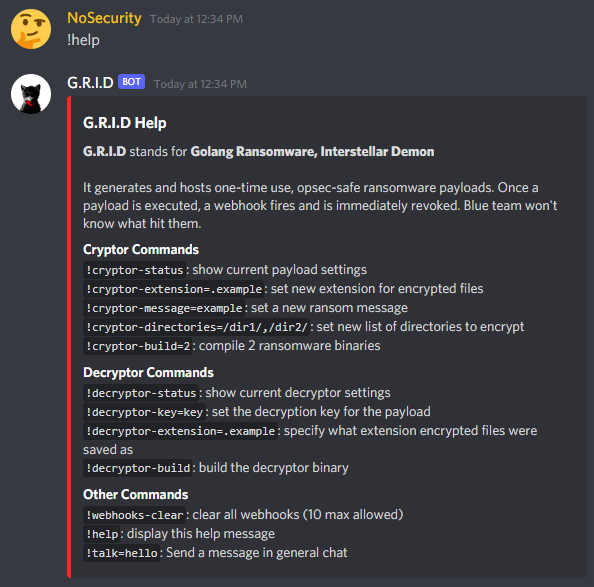

The project is done almost entirely with Golang, only exceptions being PowerShell scripts used by the bot to build the cryptor and decryptor payloads. If I were to redo the project, I would use Python to write the bot, because server-side dependencies aren’t an issue and it’s much easier to write in. The payload however must be compiled, and asking the Blue Teams nicely to install my malware’s dependencies isn’t a foolproof plan. Overall, the bot has all the necessary features the Red Team might need and its commands are listed using the !help command as such:

Building Payloads

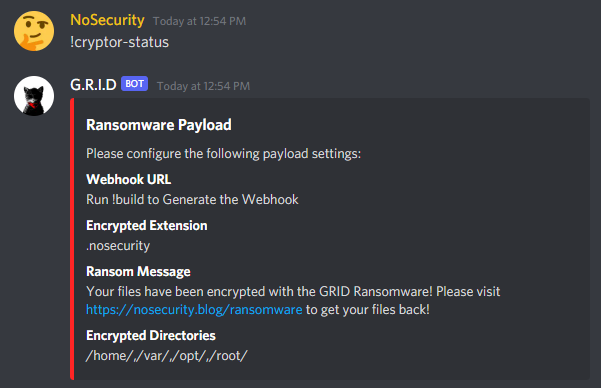

Building a payload is very straightforward with G.R.I.D and in fact you don’t even need to configure anything and you can simply use the default payload settings. Whether you use the defaults or you override them with something else, the current payload configuration can be seen using the !cryptor-status command:

The workflow for configuring the cryptor payload is also very simple. You can change the extension of encrypted files on the system with !cryptor-extension, the ransom message that gets displayed with !cryptor-message, and the directories that you want encrypted with !cryptor-directories as such:

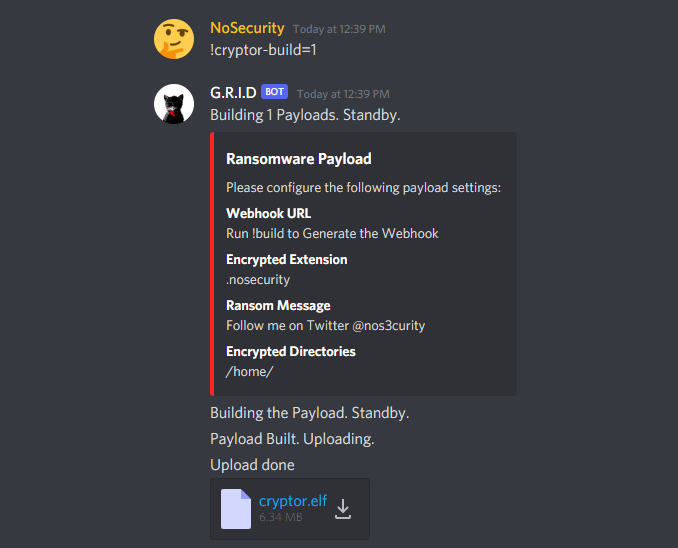

When you are ready to build the cryptor payload, simply run !cryptor-build and specify the number of executables you want generated. For obvious OPSEC reasons discussed in the Design section of this blog, the executables are one-time use, therefore if you want to hit multiple targets in quick succession, you have to get a unique payload for every target.

Finally, right click the cryptor.elf attachment and copy the link. You are now ready to terrorize the Blue Team. But what if you have a change of heart and want to help a Blue Team decrypt their files?

Getting Decryption

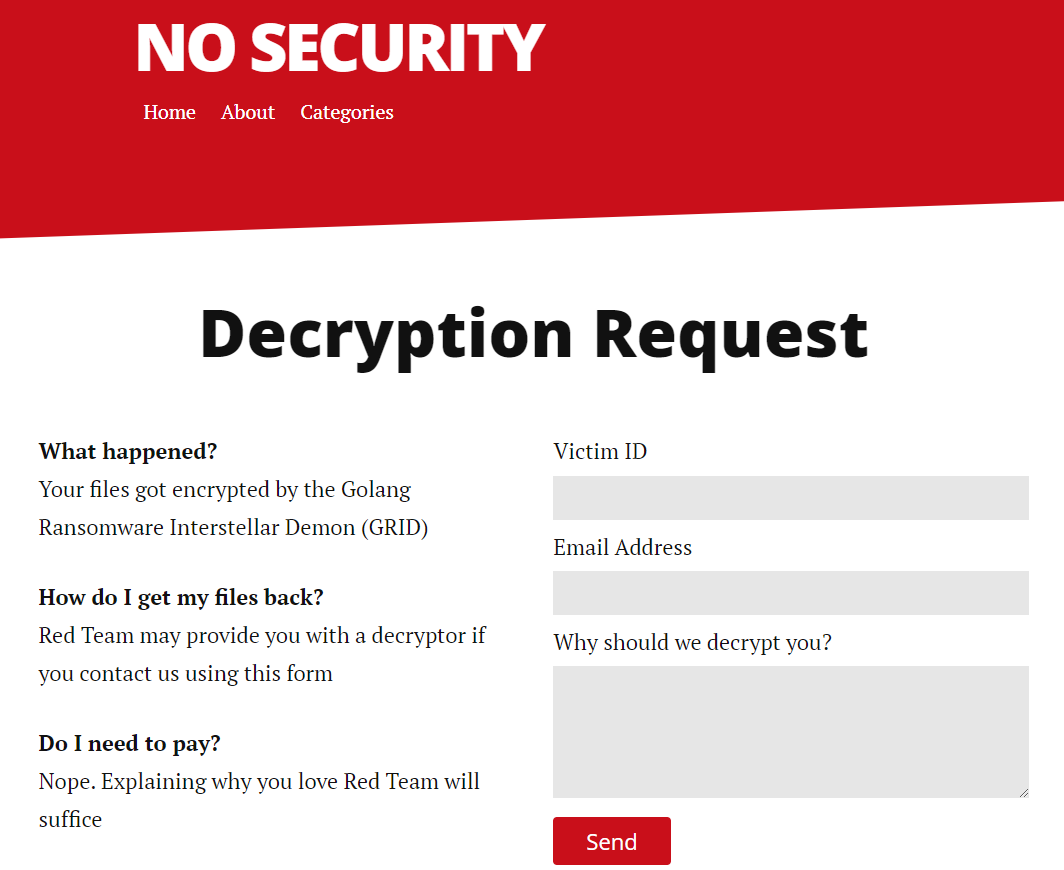

Every ransomware gang has a way for victims to contact them to discuss decryption and mine is no exception. In my case, the Blue Teams know very well who will be ransomwaring them, so there isn’t a need to hide our identity - I just host the victim contact form on my blog, as seen in the image below.

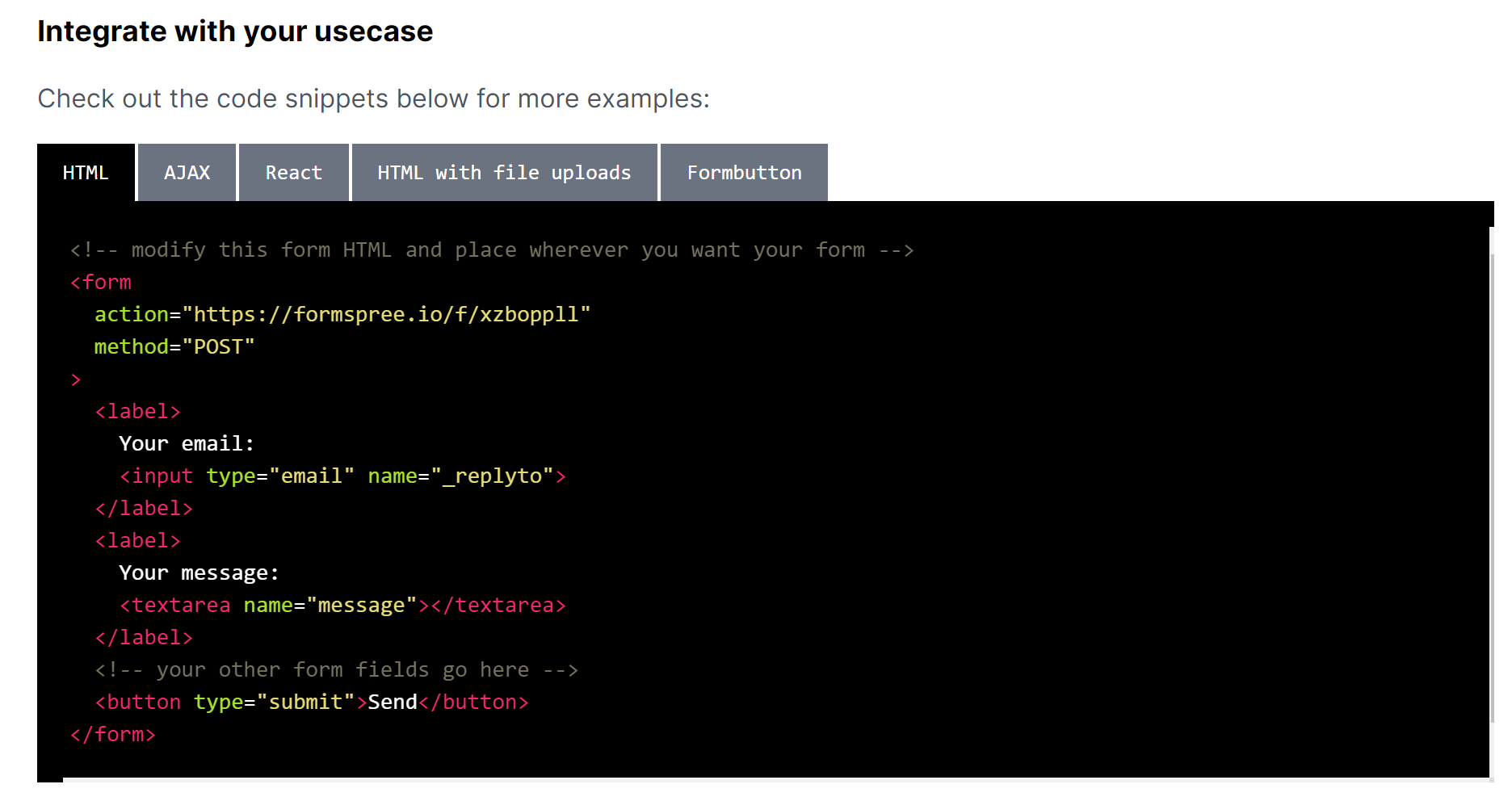

My blog runs on GitHub Pages, therefore it doesn’t run any dynamic content. I can’t stick a PHP file inside the document root and expect my code to work, but I can use Formspree to set it up. You merely need to register and create a new form - they will give you the HTML to use on the website:

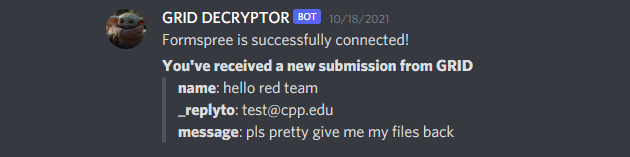

Once you set up your form, you can also go to the Plugins section and integrate it with a Discord webhook to receive notifications upon submission as such:

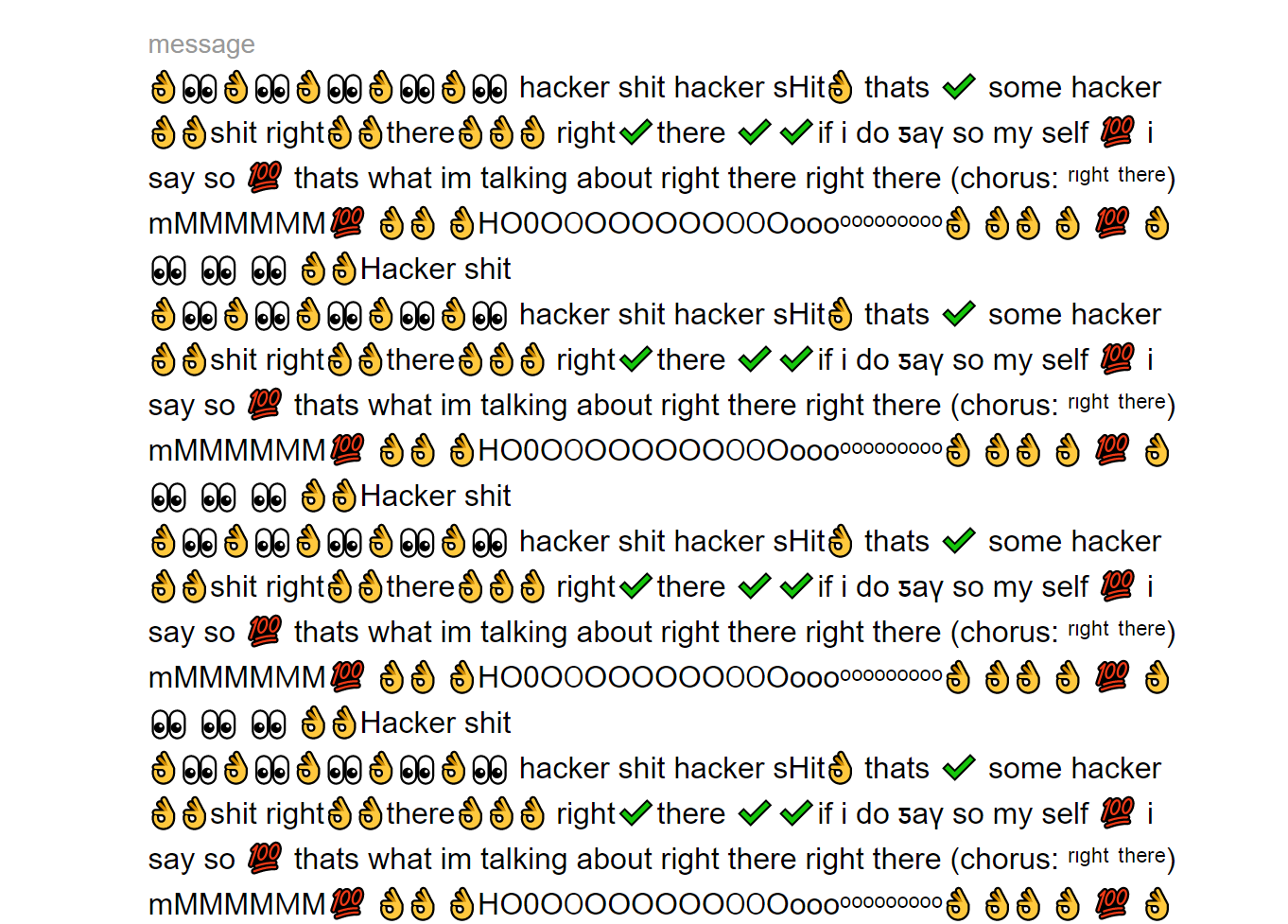

In hindsight, maybe there needs to be some kind of access control to confirm submissions are coming from valid victims:

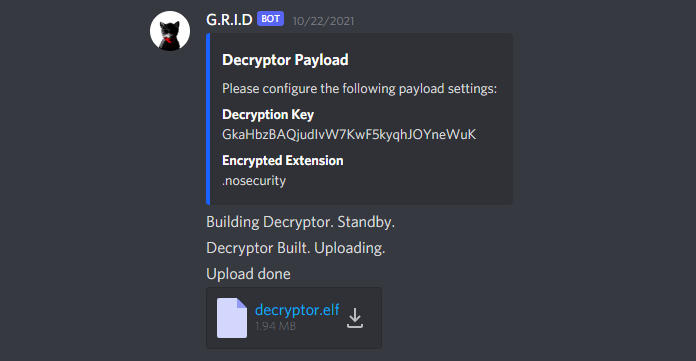

Finally, once a valid decryption request comes in and you decide to approve it, the decryptor payload may be created using familiar syntax, with !decryptor-key setting the key used to encrypt the files and !decryptor-extension setting their extension. The payload itself is then built using !decryptor-build and we once again get the ELF binary hosted on the Discord CDN, ready for our victim to download using the link we provide:

Bonus points if Blue Team asks for decryption and you send them a cryptor payload instead.

Miscellaneous Commands

When making the bot I also added some quality-of-life features, such as being able to talk as the bot in general chat using the !talk command like this:

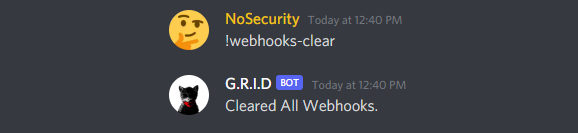

Additionally, there was a Discord limitation that I discovered - only 10 webhooks can be active for a channel at a time, so I added the !webhooks-clear command to remove any webhooks that haven’t been deleted by the bot yet (meaning their payload hasn’t fired):

Encryption

The G.R.I.D ransomware uses symmetric AES encryption, which is trivial to implement in Golang, and much better articles exist that go through the entire process of encrypting a file with it. For this section, I’d like to talk about the high-level logistics of my malware’s encryption. Key management was a major question for me, as I didn’t want Blue Team to simply run strings on my payload and get all they need to decrypt their files. To prevent that, I randomly generate the key at runtime, therefore it only exists on the victim machine while the payload is running. Golang encryption is super fast, so good luck pulling the key from memory, Blue Team. Sniffing for the key with Wireshark won’t work either, because the key travels inside the request body, which is encrypted thanks to HTTPS.

At its core, my malware has a very basic set of instructions. It recursively walks through each of the directories specified by !cryptor-directories and does a few checks to determine if a file is good to encrypt. It avoids symlinks, system files and checks whether it’s looking at a directory. If it finds a directory, it places a ransom note inside, before going in and encrypting everything in it:

func encryptDirectory(directoryPath string) {

filepath.Walk(directoryPath,

func(filePath string, fileInfo os.FileInfo, err error) error {

if !fileInfo.IsDir() {

encryptFile(filePath)

} else {

noteFile, err := os.Create("ransom_note.txt")

if err == nil {

noteFile.WriteString(ransomMessage)

} else {

fmt.Println("[!] Error creating ransom note in " + filePath)

}

}

return nil

})

}

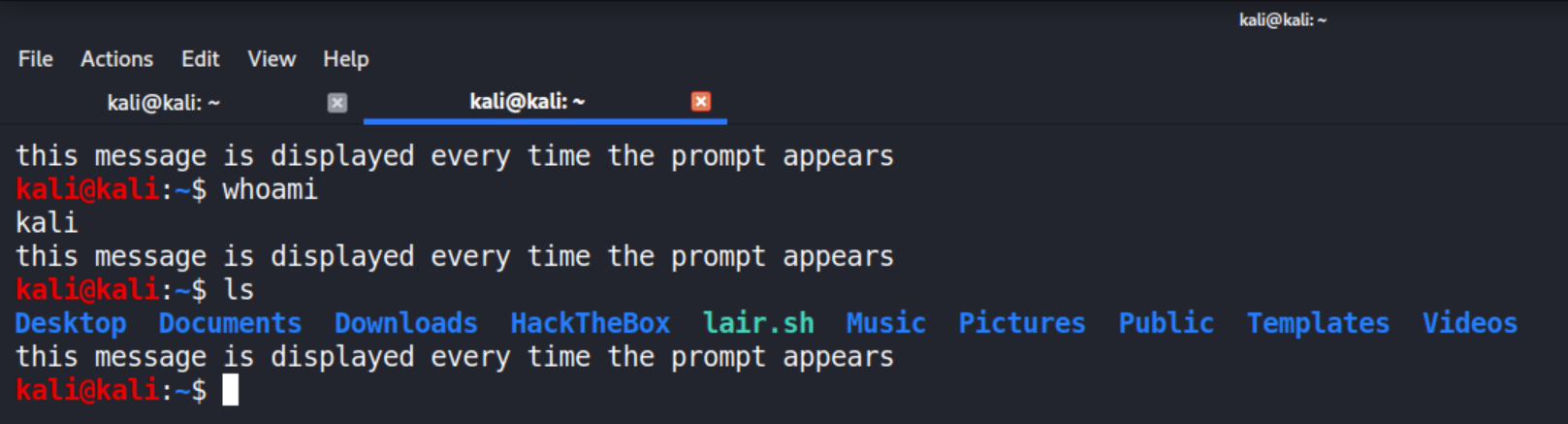

Traditionally, ransomware would change your desktop image and leave a ransomware note to give the victim instructions on what happened and how to get their files back. My project however is aimed to be strictly CLI based, so although it leaves ransom notes, the victim won’t know what happened unless they see one. I came up with a pretty funny solution to remedy this - the PROMPT_COMMAND variable. PROMPT_COMMAND is an environment variable in Bash that decides what happens every time a command prompt appears in the terminal:

If one could tamper with this variable, they could get their code executed not only when the terminal first opens, but also whenever any command is run, because the prompt reappears right after. Naturally, I thought it was hilarious to stick my ransom message into that variable and have it be echo’ed anytime the victim uses the terminal. My code currently backdoors the .bashrc file by adding an extra line to it and then kills all running bash sessions except for its own to ensure changes take effect:

func backdoorBashRc(filePath string) {

file, err := os.OpenFile(filePath, os.O_WRONLY|os.O_APPEND, 0644)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("[!] Failed opening file: " + filePath)

}

defer file.Close()

file.WriteString("PROMPT_COMMAND=\"echo '" + ransomMessage + "' ; ${PROMPT_COMMAND}\"\n")

}

Mitigation

Despite the evil nature of this project, I do ultimately want blue teams to win. Real ransomware will hit them like a truck when they graduate and start doing real security work, therefore my crappy malware is their only real opportunity to learn how to fight it, before they face it in real incidents. Here are some of my thoughts on fighting back against this particular malware for the next Red vs. Blue in Spring of 2022:

- Backup Critical Services

- The Red Team deployed this ransomware in a very targeted manner. We configured it to specifically target the

/var/www/directory and each user’s/home/directory. We went out of our way to avoid encrypting anything that would permanently brick the machine, because as a ransomware gang, we are interested in profits, not destruction. Due to the number of teams, we didn’t have time to go hunt down for any backups Blue Teams might have made, therefore as long as you had/var/www/backed up somewhere, you could just bring your services back up.

- The Red Team deployed this ransomware in a very targeted manner. We configured it to specifically target the

- Harden User and File Permissions

- The malware was developed with some flexibility and can be run as both

rootand a regular user. The significant difference here is obviously thatroothas access to everything, therefore when Red Team ran the ransomware with elevated permissions, we had the potential to encrypt everything we could find on the box. On the other hand, when we ran it as a regular user, we were limited by the existing file permissions and could only encrypt a portion of the file system. If you secure yoursudogroup and scored service file permissions, you will greatly limit our attack potential.

- The malware was developed with some flexibility and can be run as both

What will not work however, is getting antivirus software like ClamAV. My code is not public and no samples have been submitted to Virus Total, therefore no signatures exist for it. Unless you have anti-malware software performing complex heuristic checks to see what the payload does, it won’t help.

Closing Thoughts

SWIFT’s Red vs. Blue is the only academic environment at Cal Poly Pomona where students can see and experience real ransomware, so I want them to take this opportunity to learn how to combat it, because those skills will absolutely transfer to the real world, where ransomware is so prolific. If you are interested in competing or Red Teaming for the Spring Red vs. Blue event, let me know.